ON LOGIC

PLEASE NOTE, THIS PAGE IS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT

An explanation of logic and logical fallacies [1][2][3]STRUCTURE OF A LOGICAL ARGUMENT

Rhetoric is the use of language to develop a persuasive argument. Logic is the use of valid reasoning in order to illustrate an argument.

When we develop arguments, we begin with one or more premises—an idea, guess, deduction—and apply logic to illustrate a connection to a conclusion about the premise or premises. This is often called deductive reasoning. In essence, experiments test a premise, or premises, and researchers assert a conclusion or relationship based upon the test.

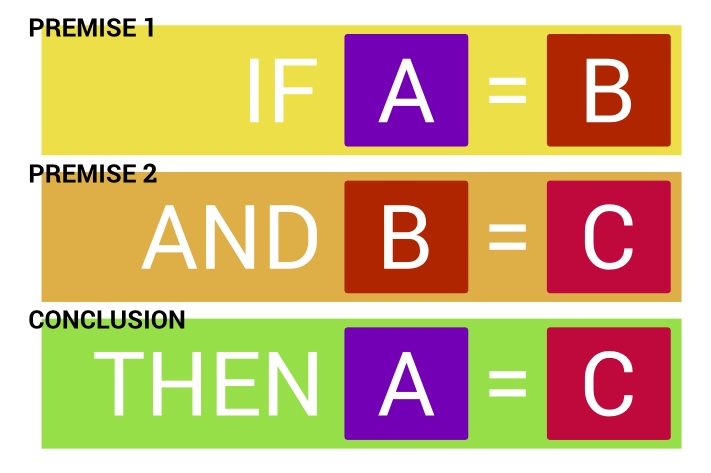

The logical structure is often represented symbolically.

PREMISE 1: A = B, AND PREMISE 2: B = C THEN (Logical connection, applying the principle of logical equivalence) CONCLUSION A = C

A valid logical argument, or sound argument, occurs when the premises are true; if all premises are true, then the conclusion is true. If one or more premise is false, the argument leads to a false conclusion.

Arguments may use wrong information, or faulty logic, to reach a conclusion that is true. Invalid—unsound—arguments to not prove a conclusion false, but removes the argument as support for the conclusion.

Researchers utilize the principles of logic when developing a hypothesis, and drawing conclusions or relationships between variables

Understanding logic will assist a anyone reviewing research, helping the reviewer to determine the validity of the research in question, the strength of the validity, whether the premises of the experiment are true, and if the researcher provides an accurate conclusions.[4]

EXAMINE YOUR PREMISES

In order for an argument to be sound all of its premises must be true.

Different people—or researchers— may start with the same premise(s), and come to different conclusions.

There are three types of potential problems with premises:

Incorrect Premise

The first, and most obvious, is that a premise can be wrong.

If one argues, for example, that evolutionary theory is false because there are no transitional fossils, that argument is unsound because the premise – no transitional fossils – is false. In fact there are copious transitional fossils.

Unestablished Premise

Another type of premise error occurs when one or more premises is an unwarranted assumption. The premise may or may not be true, but it has not been established sufficiently to serve as a premise for an argument. Identifying all the assumptions upon which an argument is dependent is often the most critical step in analyzing an argument. Frequently, different conclusions are arrived at because of differing assumptions.

For example, in my post[5] analyzing the study of the therapeutic efficacy of acupressure for insomnia relief[6], the author presents the premise that the Sea-Band device provides acupressure therapy, without ever establishing the efficacy of Sea-Ban—the authors also failed to establish acupressure as a therapy, and relied on several logical fallacies form their conclusions.

Often people will choose the assumptions that best fit the conclusion they prefer. In fact, psychological experiments show that most people start with conclusions they desire, then reverse engineer arguments to support them – a process called rationalization.

One way to resolve the problem of using assumptions as premises is to carefully identify and disclose those assumptions up front. Such arguments are often called “hypothetical.”

Disagreements here are often resolved as more information becomes available, supporting one conclusion or the other.

Hidden Premise

The third type of premise difficulty is the most insidious: the hidden premise. if a disagreement is based upon a hidden premise, then the disagreement will be irresolvable. So when coming to an impasse in resolving differences, it is a good idea to go back and see if there are any implied premises that have not been addressed.

Using transitional fossil example: Scientists believe we have many transitional fossils and evolution deniers believe that we do not. This would seem to be a straightforward factual claim easily resolvable by checking the evidence. Sometimes evolution deniers are simply ignorant of the evidence or are being intellectually dishonest. However, the more sophisticated are fully aware of the fossil evidence and use a hidden premise to deny the existence of transitional fossils.

When a paleontologist speaks of “transitional” fossils, they refer to species that occupy a space between two known species. This may be a common ancestor, in which case the transitional fossil will be more ancient than both descendant species; or it might be temporally between two species, the descendant of one and the ancestor of the other. Paleontologist often do not know if the transitional species is an actual ancestor or just closely related to the true ancestor. Because evolution is “bushy” and not linear, most species lie on an evolutionary side branch. If they fill a gap between known species, they provide evidence of an evolutionary connection, and therefore qualify as transitional. When evolution deniers say there are no transitional fossils their unstated major premise is that they are employing a different definition of transitional than is generally accepted in the scientific community. They typically define transitional as some impossible monster with half-formed and useless structures. Or, they may define transitional as only those fossils for which there is independent proof of being a true ancestor, rather than simply closely related to a direct ancestor – an impossible standard.

Another hidden premise in their argument is the notion of how many transitional fossils there should be in the fossil record. Deniers can always assume an arbitrarily high number and claim that there isn’t enough fossils to provide evidence.

LOGICAL FALLACIES

AN INTRODUCTION TO LOGICAL FALLACIES

When all of the premises of an argument are reliably true, the argument may still be invalid if the logic employed is not legitimate—this is know as a logical fallacy. There are many common logical pitfalls, when examining research or arguing in the debate club, a person must remain aware of these pitfalls and make efforts to avoid them.

HEURISTICS[7]

Humans also tend to use logical short-cuts called heuristics. These are thought processes lacking strict validity in their logic, but are true most of the time. They should not be substituted for valid logic..

Common examples of heuristics:

Anchoring and adjustment

Describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

Availability heuristic

A mental shortcut that occurs when people make judgments about the probability of events by the ease with which examples come to mind.

Representativeness heuristic

A mental shortcut used when making judgments about the probability of an event under uncertainty. Or, judging a situation based on how similar the prospects are to the prototypes the person holds in his or her mind.

Naïve diversification

When asked to make several choices at once, people tend to diversify more than when making the same type of decision sequentially.

Escalation of commitment

Describes the phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the cost, starting today, of continuing the decision outweighs the expected benefit.

Familiarity heuristic

A mental shortcut applied to various situations in which individuals assume that the circumstances underlying the past behavior still hold true for the present situation and that the past behavior thus can be correctly applied to the new situation.

COMMON LOGICAL FALLACIES

Since people often start with desired conclusions, a person attempt to support their conclusion by relying on logical fallacy—see the insomnia post.[8] When a conclusion is not true, a person must employ false premises or logical fallacies. A sound argument—with true premises and validi logic—cannot lead to a false conclusion. In order to avoid using logical fallacies to construct invalid arguments, it is necessary to understand how to identify fallacious logic.

Below is a list of the most common logical fallacies, with examples of each.

Ad hominem

An ad hominem argument is any that attempts to counter another’s claims or conclusions by attacking the person, rather than addressing the argument itself. For example, Skinner’s theory of behavior was wrong because he was an evil, emotionless man wishing to exert control on people around him.

A common form of this fallacy is also frequently present in the arguments of conspiracy theorists. For example, they may argue that the government must be lying because they are corrupt.

Poisoning the Well

The term “poisoning the well” refers to a form of ad hominem fallacy. This is an attempt to discredit the argument of another by implying that they possess an unsavory trait, or that they are affiliated with other beliefs or people that are wrong or unpopular. A common form of this also has its own name – Godwin’s Law or the reductio ad Hitlerum. This refers to an attempt at poisoning the well by drawing an analogy between another’s position and Hitler or the Nazis.

Ad ignorantiam

The argument from ignorance states that a specific belief is true because we don’t know that it isn’t true. Defenders of extrasensory perception, for example, will often overemphasize how much we do not know about the human brain. It is therefore possible, they argue, that the brain may be capable of transmitting signals at a distance.

In order to make a positive claim, positive evidence must be presented for the specific claim. The absence of another explanation only means that we do not know – it doesn’t mean we get to make up a specific explanation.

Argument from authority

The basic structure of such arguments is as follows: Professor X believes A, Professor X speaks from authority, therefore A is true. This argument is often implied by emphasizing many years of experience, or formal degrees held by the individual making a specific claim. The converse of this argument is sometimes used, that someone does not possess authority, and therefore their claims must be false.

This is a complex logical fallacy. It is legitimate to consider the training and experience of an individual when examining their assessment of a particular claim. Also, a consensus of scientific opinion does carry some legitimate authority. But it is still possible for highly educated individuals, and a broad consensus to be wrong – speaking from authority does not make a claim true.

There are many subtypes of the argument from authority, essentially referring to the implied source of authority. A common example is the argument ad populum – a belief must be true because it is popular, essentially assuming the authority of the masses. Another example is the argument from antiquity – a belief has been around for a long time and therefore must be true.

For example, agaom from the insomnia[9] article: “Among the nondrug therapies for insomnia, acupressure, a method used for over 5000 years in Eastern medicine, is becoming increasingly popular worldwide.” In this one statement, the researcher uses an argument from antiquity and an argument ad populum—this statement also “Begs the Question.”

Argument from final Consequences/Teleological

Such arguments (also called teleological) are based on a reversal of cause and effect, because they argue that something is caused by the ultimate effect that it has, or purpose that is serves. Creationists have argued, for example, that evolution must be wrong because if it were true it would lead to immorality.

Argument from Design

One type of teleological argument is the argument from design. For example, the universe has all the properties necessary to support live, therefore it was designed specifically to support life—and therefore had a designer.

Argument from Personal Incredulity

This argument occurs when a person claims something not to be true, because they cannot explain or understand it. For example, a Psychodynamic psychologist might state that they do not understand the complexity of human behavior as explained by Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning, and therefore operant conditioning does not explain human behavior.

Begging the Question/Claim

The term “begging the question” is often misused to mean “raises the question,” (and common use will likely change, or at least add this new, definition). The intended meaning is to assume a conclusion in one’s question or claim.

A conclusion in a premise or question is added to the argument

Using an example form Argument from Authority, “Among the nondrug therapies for insomnia, acupressure, a method used for over 5000 years in Eastern medicine, is becoming increasingly popular worldwide.”[10] Without established efficacy, the researcher states that acupressure provides therapeutic relief of insominia.

Another example of begging the question occurred on the Dr. Oz Show, when Dr. Oz[11] asked Dr. Steven Novella[12], “What are alternative medicine ‘holdouts’ afraid of?” This question assumes alternative medicine has a become the majority position and that acceptance is inevitable.

Confusing association with causation

This is similar to the post-hoc fallacy in that it assumes cause and effect for two variables simply because they occur together. This fallacy is often used to give a statistical correlation a causal interpretation. For example, during the 1990’s both religious attendance and illegal drug use have been on the rise. It would be a fallacy to conclude that therefore, religious attendance causes illegal drug use. It is also possible that drug use leads to an increase in religious attendance, or that both drug use and religious attendance are increased by a third variable, such as an increase in societal unrest. It is also possible that both variables are independent of one another, and it is mere coincidence that they are both increasing at the same time.

This fallacy, however, has a tendency to be abused, or applied inappropriately, to deny all statistical evidence. In fact this constitutes a logical fallacy in itself, the denial of causation. This abuse takes two basic forms. The first is to deny the significance of correlations that are demonstrated with prospective controlled data, such as would be acquired during a clinical experiment. The problem with assuming cause and effect from mere correlation is not that a causal relationship is impossible, it’s just that there are other variables that must be considered and not ruled out a-priori. A controlled trial, however, by its design attempts to control for as many variables as possible in order to maximize the probability that a positive correlation is in fact due to a causation.

Further, even with purely epidemiological, or statistical, evidence it is still possible to build a strong scientific case for a specific cause. The way to do this is to look at multiple independent correlations to see if they all point to the same causal relationship. For example, it was observed that cigarette smoking correlates with getting lung cancer. The tobacco industry, invoking the “correlation is not causation” logical fallacy, argued that this did not prove causation. They offered as an alternate explanation “factor x”, a third variable that causes both smoking and lung cancer. But we can make predictions based upon the smoking causes cancer hypothesis. If this is the correct causal relationship, then duration of smoking should correlate with cancer risk, quitting smoking should decrease cancer risk, smoking unfiltered cigarettes should have a higher cancer risk than filtered cigarettes, etc. If all of these correlations turn out to be true, which they are, then we can triangulate to the smoking causes cancer hypothesis as the most likely possible causal relationship and it is not a logical fallacy to conclude from this evidence that smoking probably causes lung cancer.

Confusing currently unexplained with unexplainable

Person’s utilizing this fallacy believe a currently unexplainable idea can never be explained. Just because an adequate explanation for a phenomenon does not currently exist, it does not mean that the phenomena is forever unexplainable, or that it therefore defies the laws of nature or requires a paranormal explanation.

An example of this is the “God of the Gaps” strategy of creationists that whatever we cannot currently explain is unexplainable and was therefore an act of god.

False Analogy

Analogies are very useful as they allow us to draw lessons from the familiar and apply them to the unfamiliar. Life is like a box of chocolate – you never know what you’re going to get.

A false analogy is an argument based upon an assumed similarity between two things, people, or situations when in fact the two things being compared are not similar in the manner invoked. Saying that the probability of a complex organism evolving by chance is the same as a tornado ripping through a junkyard and created a 747 by chance is a false analogy. Evolution, in fact, does not work by chance but is the non-random accumulation of favorable changes.

Creationists also make the analogy between life and your home, invoking the notion of thermodynamics or entropy. Over time your home will become messy, and things will start to break down. The house does not spontaneously become more clean or in better repair.

The false analogy here is that a home is an inanimate collection of objects. Whereas life uses energy to grow and reproduce – the addition of energy to the system of life allows for the local reduction in entropy – for evolution to happen.

Another way in which false analogies are invoked is to make an analogy between two things that are in fact analogous in many ways – just not the specific way being invoked in the argument. Just because two things are analogous in some ways does not mean they are analogous in every way.

False Continuum

The idea that because there is no definitive demarcation line between two extremes, that the distinction between the extremes is not real or meaningful: There is a fuzzy line between cults and religion, therefore they are really the same thing.

False Dichotomy

Arbitrarily reducing a set of many possibilities to only two. For example, evolution is not possible, therefore we must have been created (assumes these are the only two possibilities). This fallacy can also be used to oversimplify a continuum of variation to two black and white choices. For example, science and pseudoscience are not two discrete entities, but rather the methods and claims of all those who attempt to explain reality fall along a continuum from one extreme to the other. Another example, People can either stop using cars or destroy the earth.

Genetic Fallacy

The term “genetic” does not refer to DNA or genes, but to history (and therefore a connection through the concept of inheritance). This fallacy assumes that something’s current utility is dictated by and constrained by its historical utility.

For example, a person might believe the Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally designed by Hitler’s army.

Inconsistency

Applying criteria or rules to one belief, claim, argument, or position but not to others. For example, some consumer advocates argue that we need stronger regulation of prescription drugs to ensure their safety and effectiveness, but at the same time argue that medicinal herbs should be sold with no regulation for either safety or effectiveness.

No True Scotsman

This fallacy is a form of circular reasoning, in that it attempts to include a conclusion about something in the very definition of the word itself. It is therefore also a semantic argument.

The term comes from the example: If Ian claims that all Scotsman are brave, and you provide a counter example of a Scotsman who is clearly a coward, Ian might respond, “Well, then, he’s no true Scotsman.” In essence Ian claims that all Scotsman are brave by including bravery in the definition of what it is to be a Scotsman. This argument does not establish any facts or new information, and is limited to Ian’s definition of the word, “Scotsman.”

Non-Sequitur

In Latin this term translates to “doesn’t follow”. This refers to an argument in which the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the premises. In other words, a logical connection is implied where none exists.

Post-hoc ergo propter hoc

This fallacy infers causation from a chronological relationship.

The basic format: A preceded B, therefore A caused B, and therefore assumes cause and effect for two events just because they are temporally related.

I drank bottled water and now I am sick, so the water must have made me sick.

Reductio ad absurdum

In formal logic, the reductio ad absurdum is a legitimate argument. It follows the form that if the premises are assumed to be true it necessarily leads to an absurd (false) conclusion and therefore one or more premises must be false. The term is now often used to refer to the abuse of this style of argument, by stretching the logic in order to force an absurd conclusion. For example a UFO enthusiast once argued that if I am skeptical about the existence of alien visitors, I must also be skeptical of the existence of the Great Wall of China, since I have not personally seen either. This is a false reductio ad absurdum because he is ignoring evidence other than personal eyewitness evidence, and also logical inference. In short, being skeptical of UFO’s does not require rejecting the existence of the Great Wall.

Slippery Slope

This logical fallacy is the argument that a position is not consistent or tenable because accepting the position means that the extreme of the position must also be accepted. But moderate positions do not necessarily lead down the slippery slope to the extreme.

Special pleading, or ad-hoc reasoning

This is a subtle fallacy which is often difficult to recognize. In essence, it is the arbitrary introduction of new elements into an argument in order to fix them so that they appear valid. A good example of this is the ad-hoc dismissal of negative test results. For example, one might point out that ESP has never been demonstrated under adequate test conditions, therefore ESP is not a genuine phenomenon. Defenders of ESP have attempted to counter this argument by introducing the arbitrary premise that ESP does not work in the presence of skeptics. This fallacy is often taken to ridiculous extremes, and more and more bizarre ad hoc elements are added to explain experimental failures or logical inconsistencies.

Straw Man

A straw man argument attempts to counter a position by attacking a different position – usually one that is easier to counter. The arguer invents a caricature of his opponent’s position – a “straw man” – that is easily refuted, but not the position that his opponent actually holds.

For example, defenders of alternative medicine often argue that skeptics refuse to accept their claims because they conflict with their world-view. If “Western” science cannot explain how a treatment works, then it is dismissed out-of-hand. If you read skeptical treatment of so-called “alternative” modalities, however, you will find the skeptical position much more nuanced than that.

Claims are not a-prior dismissed because they are not currently explained by science. Rather, in some cases (like homeopathy) there is a vast body of scientific knowledge that says that homeopathy is not possible. Having an unknown mechanism is not the same thing as demonstrably impossible (at least as best as modern science can tell). Further, skeptical treatments of homeopathy often thoroughly review the clinical evidence. Even when the question of mechanism is put aside, the evidence shows that homeopathic remedies are indistinguishable from placebo – which means they do not work.

Tautology/Circular Argument

Tautology in formal logic refers to a statement that must be true in every interpretation by its very construction. In rhetorical logic, it is an argument that utilizes circular reasoning, which means that the conclusion is also its own premise. Typically the premise is simply restated in the conclusion, without adding additional information or clarification. The structure of such arguments is A=B therefore A=B, although the premise and conclusion might be formulated differently so it is not immediately apparent as such. For example, saying that therapeutic touch works because it manipulates the life force is a tautology because the definition of therapeutic touch is the alleged manipulation (without touching) of the life force.

The Fallacy Fallacy

As I mentioned near the beginning of this article, just because someone invokes an unsound argument for a conclusion, that does not necessarily mean the conclusion is false. A conclusion may happen to be true even if an argument used to support is is not sound. I may argue, for example, Obama is a Democrat because the sky is blue – an obvious non-sequitur. But the conclusion, Obama is a Democrat, is still true.

Related to this, and common in the comments sections of blogs, is the position that because some random person on the internet is unable to defend a position well, that the position is therefore false. All that has really been demonstrated is that the one person in question cannot adequately defend their position.

This is especially relevant when the question is highly scientific, technical, or requires specialized knowledge. A non-expert likely does not have the knowledge at their fingertips to counter an elaborate, but unscientific, argument against an accepted science. “If you (a lay person) cannot explain to me,” the argument frequently goes, “exactly how this science works, then it is false.”

Rather, such questions are better handled by actual experts. And, in fact, intellectual honesty requires that at least an attempt should be made to find the best evidence and arguments for a position, articulated by those with recognized expertise, and then account for those arguments before a claim is dismissed.

Red Herring

This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. For example: The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families?

The Moving Goalpost

A method of denial arbitrarily moving the criteria for “proof” or acceptance out of range of whatever evidence currently exists. If new evidence comes to light meeting the prior criteria, the goalpost is pushed back further – keeping it out of range of the new evidence. Sometimes impossible criteria are set up at the start – moving the goalpost impossibly out of range -for the purpose of denying an undesirable conclusion.

Tu quoque

Literally, you too. This is an attempt to justify wrong action because someone else also does it. “My evidence may be invalid, but so is yours.”

NOTE: The bulk of the source material from this page comes from the resources page on www.theskepticsguide.org. Descriptions have been modified to better fit the theme of GETPSYCHED, and to included other resources and information.

________________

[1] Logical fallacies. Retrieved from http://www.theskepticsguide.org/resources/logical-fallacies

[2] Logic. Retrieved November 18, 2013 from Wikipedia: http://en.wikpedia..org/wiki/Logic

[3] Logical fallacies. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/659/03/

[4] Ingham-Broomfield, R. (2008). A nurses’ guide to the critical reading of research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 6(1), 102-109.

[5] Link to post and article

[6] Link to post and article

[7]Heuristic. Retrieved November 17, 2013 from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heuristic

[8] Insomnia post

[9] post

[10] post

[11] See http://www.doctoroz.com/

[12] See http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/about/